Tuesday, February 16, 2010

Transitions

Ramanuja might have been watching pigeons the entire time. "We are thinking of going to London," he said softly. He wore a hospital gown. He was sitting up in bed with his hands cupped together lightly on his blanketed lap. Dehydration quenched, he appeared more energetic and fully alive. Almost absently, he asked a question. "Did something happen?"

Thursday, February 4, 2010

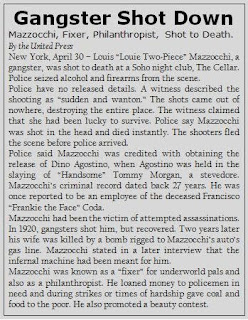

30 April, in the Times

Saturday, January 23, 2010

Mont Sunday

A Family Matter

I.

“This I cannot belief. Vhen vill you get mature?”

The nice fellow in the tuxedo at The Cellar had only stayed with Emma and Cati long enough apply first aid and to staunch the bleeding. After that, because they could both walk and there were far too many other injuries for him to ignore, he sent them to the hospital. However, Cati was not daft, and she knew that for a person of her standing to simply show up at a hospital wounded would attract problematic attention. “It’s not like we’re famous or nuthin’,” Emma said, “but we’ll make the news, and your mother would murder us.” A moderately painful forty minutes later, and Cati was snoozing on a morphine drip administered by the family physician, Harmick, in a bedroom at her mother’s house.

The good doctor had alerted Cati’s mother, Anica, and when morning came the elder Predoviciu decided that there should be some light shed on her daughter’s nighttime injuries. Emma, who had spent the night in a chair at Cati’s side without the benefit of a sedative, had helped Cati by explaining that it was all just an unfortunate accident. “I blame myself,” she had ineffectively offered. “We just shouldn’t have been at that joint, it’s got such a seedy reputa-tation.”

Cati’s mother was not much of a drinker, but nor was she a teetotaler; that her daughter had been at The Cellar was no problem in and of itself for her, for, despite Emma’s plea, it was actually more or less reputa-table as far as speakeasies went. She had no choice but to accept the women’s account of how Cati had been injured, which was in some ways more true than not. But what Anica Predoviciu could not accept was the fact that her daughter, old enough to have been a married woman at one time, had been reckless enough in her carousing to have met with some serious misfortune. She knew that Cati had passed through some restless, unruly years, but she had thought that those were behind her. If the young woman went out at night with her friends, took a few lovers, enjoyed her life before she got married again – well, who could blame her, she was young. But things were clearly more serious now. Anica hummed unhappily to herself when Cati rolled over in bed and she saw how the bruise had grown on the young woman’s forehead overnight. She sent Emma away.

Now it was just Cati and her mother. Cati wanted to tell her the truth. Barring that, she wanted to protest her mother’s desire to rein her in. She had already tried reminding her mother exactly how old she was, that she was a grown woman, she could make her own decisions. How often did she wish she could let her mother know just how poor her own decisions could sometimes be – in choosing a husband for Cati. But she knew that, unless she was willing to explain every aspect of her misadventures to her mother, then she’d have to bear with the situation at hand, including her mother’s wrath and whatever measures she might take to restrict Cati’s access to the family fortunes and freedom. And to explain everything would be impossible, maybe even dangerous. Impossible because of the audacious character of the events that Cati would have to relate to her dear mother in order to actually account for anything; impossible because Cati could not bear any more embarrassment for the many, many poor decisions that she had made over the past few days.

“Hm hmm hmmm. Hm? Vhen vill you begin to be responsibile for the name you wear? ‘Predoviciu’ – dear, ve are not common workers, this name is our labor and livelihood.”

Responsible? Cati thought. The decisions were only poor in retrospect, and they were of good moral quality. Many of them had been made out of necessity. It was not Cati’s fault that the cabbie had tried to kidnap her. Nor was it her fault that a wizard – a real, wizard with magic spells and everything in this day and age! – had set his own evil intentions against her. Nor was Margaret’s death Cati’s doing. No, not just Margaret’s death – Mags had been murdered. Remembering that she had been working against a murderer, and not just indulging her curiosity and flaunting her status, helped to keep Cati’s morale up.

“You must think,” Anica said, viciously gesturing at her own cranium. “Ve remain vealfy, ve remain who ve are because we keep this name on good condition.”

Somewhere inside her, Cati knew that following up on Mags’s death had been the right thing to do. Why, if it hadn’t been for Henri, Thelonius, and herself, the police would never have captured the murderer. Yes, Cati conceded to herself, she had made some decisions that were not in the best interest of her mother, but the family as a whole was quite sturdy, and, unlike many other wealthy immigrant families from the East, had managed to avoid any major public scandals.

“People of vorth know that they can trust us.”

That was true. Henri had been willing to rush to her side. Thelonius, too, risked his life for her, taking that vial full of mercury (but not mercury, something far more dangerous, valuable, and interesting). And Cati had not, in her most desperate moment, abandoned either of them.

“They cannot gif us that trust if we are caught in the newspapers running around town, caforting with drunk. And here you are now. You look terrible, you look –”

“Like I’ve been in an auto accident,” Cati interjected with no small amount of irritation in her voice.

The elder Predoviciu pursed her lips and clutched her hands to her lap. After a moment, she said, “I am too harsh, I know. I know. I am sorry.” Anica did not know. It was better that way. “But who do I blame then? Who does a mother to hold for this? It is my fault.”

Could anybody be held accountable? Cati had two names in mind: Ramanuja and White. If Ramanuja hadn’t brought Mags into his circle of hocus pocus – apparently real hocus pocus, Cati reminded herself – then she’d still be alive. And this White character. If he hadn’t –

The curtain of morphine and pain and annoyance at her mother lifted suddenly. White – the name that the bathroom attendant had sputtered in surprise when the man in grey had ended his time-spell. White – wasn’t that was the name of Mags’s fiancé. Jacqueline had said so. Until that moment, Cati had never suspected, but now it was all quite clear, and it was too much of a coincidence.

“Ecatarina, I vant you to leaf for a vhile. There is a place in the mountains. A friend of mine, Madam Bakker, she owns it. Vhen you are vell enough, I am going to send you there vith Doctor Harmick.”

Cati wanted to protest, but her mother saw it coming and cut her off.

“You vill. You need to get avay from the bad influences of the city. You haf no choice. As long as you go, I vill not cut you off. Do this for your health,” the elder pleaded. “Cati my dear, do it for our family name and for me. You are doing too much trouble in this city. This is final.” She left, joining the shadow of Dumitru in the hallway.

II.

Cati knew Madam Bakker. Hers was very old New York Dutch money, but a few generations of Bakker men given to financial misadventure had worn away the greater part of that family’s fortunes. For this reason, Madam Bakker found it socially permissible to mix with the nouveau riche and the immigrant wealthy. She was a pleasant woman, Cati thought, broad-minded and eccentric. A lover of cats and classical literature. But Cati had never been to her upstate home, and she was not sure that leaving the city, leaving Thelonius, Henri, Ramanuja, and White was the right thing to do.

She had only been considering this for a minute before Emma quietly turned the knob to Cati’s room and slunk around the door like a cat. “I heard everything.” She sat down at Cati’s side, in the very seat in which she had slept the night before. “This name, this name, this name!” Emma knew the lecture well, but what she said next suggested to Cati that Emma had been impressed by the elder Predoviciu’s determination. “I’ll go with you if you want. But, lady,” she said, trying to sound jovial, “you gotta come clean with me. What’s goin’ on? There’s somethin’ to those two fellas that you’re telling me. Cati?”

Cati drew breath. Was it worth explaining everything to Emma? Could Emma grasp the truth? She wished she could talk to Henri and Thelonius. This time she wouldn’t blame them for not telling her what was going on; she was beginning to piece things together for herself. Did they know who White was? Emma would be familiar with the name. But – would she even believe Cati?

Before Cati could think of an answer to her friend’s question, Emma clucked and touched Cati’s bandaged head. “Oh!” She adjusted the wrappings applied by Harmick. “You’re coming a little loose here.”

(The date is 30 April, 1924, and the time is around ten o’clock. Cati and Emma are in Anica and Dumitru Predoviciu’s house in the Upper East Side. Of course Cati is not being held prisoner, but Harmick’s advice is for a few days of bed rest before moving onto Madame Bakker’s home. Aside from the trip to Madame Bakker’s home, any attempts to leave the care of Dr. Harmick (or another physician) will make it more difficult for Cati to heal her rather serious wounds. Her current hit point total is 5 hit points.

Cati can leave Harmick’s care at any time, but her healing will be seriously compromised. Taking it easy for a while is the best plan for her physically, but bed rest limits her options. Without leaving Harmick’s care, Cati could spend some time studying any documents she may have collected. (If they’re in her own house, then Emma can go get them for her, or her maid can bring them.) She can also make phone calls, and that might be all it takes to find out what happened to Thelonius or Henri. Calling hospitals and the police are good starts. It would also make sense for Cati to be interested in finding out more about White, which she might accomplish with a few creative phone calls to Mags Whitcombe’s or her own friends. If she wants to check in on Ramanuja, she really only needs to call St. Lawrence’s Hospital. Depending on how frank Cati wants to be with her, she might even send Emma out on various errands.

See the out of game blog for posting awards and xp.)

“This I cannot belief. Vhen vill you get mature?”

The nice fellow in the tuxedo at The Cellar had only stayed with Emma and Cati long enough apply first aid and to staunch the bleeding. After that, because they could both walk and there were far too many other injuries for him to ignore, he sent them to the hospital. However, Cati was not daft, and she knew that for a person of her standing to simply show up at a hospital wounded would attract problematic attention. “It’s not like we’re famous or nuthin’,” Emma said, “but we’ll make the news, and your mother would murder us.” A moderately painful forty minutes later, and Cati was snoozing on a morphine drip administered by the family physician, Harmick, in a bedroom at her mother’s house.

The good doctor had alerted Cati’s mother, Anica, and when morning came the elder Predoviciu decided that there should be some light shed on her daughter’s nighttime injuries. Emma, who had spent the night in a chair at Cati’s side without the benefit of a sedative, had helped Cati by explaining that it was all just an unfortunate accident. “I blame myself,” she had ineffectively offered. “We just shouldn’t have been at that joint, it’s got such a seedy reputa-tation.”

Cati’s mother was not much of a drinker, but nor was she a teetotaler; that her daughter had been at The Cellar was no problem in and of itself for her, for, despite Emma’s plea, it was actually more or less reputa-table as far as speakeasies went. She had no choice but to accept the women’s account of how Cati had been injured, which was in some ways more true than not. But what Anica Predoviciu could not accept was the fact that her daughter, old enough to have been a married woman at one time, had been reckless enough in her carousing to have met with some serious misfortune. She knew that Cati had passed through some restless, unruly years, but she had thought that those were behind her. If the young woman went out at night with her friends, took a few lovers, enjoyed her life before she got married again – well, who could blame her, she was young. But things were clearly more serious now. Anica hummed unhappily to herself when Cati rolled over in bed and she saw how the bruise had grown on the young woman’s forehead overnight. She sent Emma away.

Now it was just Cati and her mother. Cati wanted to tell her the truth. Barring that, she wanted to protest her mother’s desire to rein her in. She had already tried reminding her mother exactly how old she was, that she was a grown woman, she could make her own decisions. How often did she wish she could let her mother know just how poor her own decisions could sometimes be – in choosing a husband for Cati. But she knew that, unless she was willing to explain every aspect of her misadventures to her mother, then she’d have to bear with the situation at hand, including her mother’s wrath and whatever measures she might take to restrict Cati’s access to the family fortunes and freedom. And to explain everything would be impossible, maybe even dangerous. Impossible because of the audacious character of the events that Cati would have to relate to her dear mother in order to actually account for anything; impossible because Cati could not bear any more embarrassment for the many, many poor decisions that she had made over the past few days.

“Hm hmm hmmm. Hm? Vhen vill you begin to be responsibile for the name you wear? ‘Predoviciu’ – dear, ve are not common workers, this name is our labor and livelihood.”

Responsible? Cati thought. The decisions were only poor in retrospect, and they were of good moral quality. Many of them had been made out of necessity. It was not Cati’s fault that the cabbie had tried to kidnap her. Nor was it her fault that a wizard – a real, wizard with magic spells and everything in this day and age! – had set his own evil intentions against her. Nor was Margaret’s death Cati’s doing. No, not just Margaret’s death – Mags had been murdered. Remembering that she had been working against a murderer, and not just indulging her curiosity and flaunting her status, helped to keep Cati’s morale up.

“You must think,” Anica said, viciously gesturing at her own cranium. “Ve remain vealfy, ve remain who ve are because we keep this name on good condition.”

Somewhere inside her, Cati knew that following up on Mags’s death had been the right thing to do. Why, if it hadn’t been for Henri, Thelonius, and herself, the police would never have captured the murderer. Yes, Cati conceded to herself, she had made some decisions that were not in the best interest of her mother, but the family as a whole was quite sturdy, and, unlike many other wealthy immigrant families from the East, had managed to avoid any major public scandals.

“People of vorth know that they can trust us.”

That was true. Henri had been willing to rush to her side. Thelonius, too, risked his life for her, taking that vial full of mercury (but not mercury, something far more dangerous, valuable, and interesting). And Cati had not, in her most desperate moment, abandoned either of them.

“They cannot gif us that trust if we are caught in the newspapers running around town, caforting with drunk. And here you are now. You look terrible, you look –”

“Like I’ve been in an auto accident,” Cati interjected with no small amount of irritation in her voice.

The elder Predoviciu pursed her lips and clutched her hands to her lap. After a moment, she said, “I am too harsh, I know. I know. I am sorry.” Anica did not know. It was better that way. “But who do I blame then? Who does a mother to hold for this? It is my fault.”

Could anybody be held accountable? Cati had two names in mind: Ramanuja and White. If Ramanuja hadn’t brought Mags into his circle of hocus pocus – apparently real hocus pocus, Cati reminded herself – then she’d still be alive. And this White character. If he hadn’t –

The curtain of morphine and pain and annoyance at her mother lifted suddenly. White – the name that the bathroom attendant had sputtered in surprise when the man in grey had ended his time-spell. White – wasn’t that was the name of Mags’s fiancé. Jacqueline had said so. Until that moment, Cati had never suspected, but now it was all quite clear, and it was too much of a coincidence.

“Ecatarina, I vant you to leaf for a vhile. There is a place in the mountains. A friend of mine, Madam Bakker, she owns it. Vhen you are vell enough, I am going to send you there vith Doctor Harmick.”

Cati wanted to protest, but her mother saw it coming and cut her off.

“You vill. You need to get avay from the bad influences of the city. You haf no choice. As long as you go, I vill not cut you off. Do this for your health,” the elder pleaded. “Cati my dear, do it for our family name and for me. You are doing too much trouble in this city. This is final.” She left, joining the shadow of Dumitru in the hallway.

II.

Cati knew Madam Bakker. Hers was very old New York Dutch money, but a few generations of Bakker men given to financial misadventure had worn away the greater part of that family’s fortunes. For this reason, Madam Bakker found it socially permissible to mix with the nouveau riche and the immigrant wealthy. She was a pleasant woman, Cati thought, broad-minded and eccentric. A lover of cats and classical literature. But Cati had never been to her upstate home, and she was not sure that leaving the city, leaving Thelonius, Henri, Ramanuja, and White was the right thing to do.

She had only been considering this for a minute before Emma quietly turned the knob to Cati’s room and slunk around the door like a cat. “I heard everything.” She sat down at Cati’s side, in the very seat in which she had slept the night before. “This name, this name, this name!” Emma knew the lecture well, but what she said next suggested to Cati that Emma had been impressed by the elder Predoviciu’s determination. “I’ll go with you if you want. But, lady,” she said, trying to sound jovial, “you gotta come clean with me. What’s goin’ on? There’s somethin’ to those two fellas that you’re telling me. Cati?”

Cati drew breath. Was it worth explaining everything to Emma? Could Emma grasp the truth? She wished she could talk to Henri and Thelonius. This time she wouldn’t blame them for not telling her what was going on; she was beginning to piece things together for herself. Did they know who White was? Emma would be familiar with the name. But – would she even believe Cati?

Before Cati could think of an answer to her friend’s question, Emma clucked and touched Cati’s bandaged head. “Oh!” She adjusted the wrappings applied by Harmick. “You’re coming a little loose here.”

(The date is 30 April, 1924, and the time is around ten o’clock. Cati and Emma are in Anica and Dumitru Predoviciu’s house in the Upper East Side. Of course Cati is not being held prisoner, but Harmick’s advice is for a few days of bed rest before moving onto Madame Bakker’s home. Aside from the trip to Madame Bakker’s home, any attempts to leave the care of Dr. Harmick (or another physician) will make it more difficult for Cati to heal her rather serious wounds. Her current hit point total is 5 hit points.

Cati can leave Harmick’s care at any time, but her healing will be seriously compromised. Taking it easy for a while is the best plan for her physically, but bed rest limits her options. Without leaving Harmick’s care, Cati could spend some time studying any documents she may have collected. (If they’re in her own house, then Emma can go get them for her, or her maid can bring them.) She can also make phone calls, and that might be all it takes to find out what happened to Thelonius or Henri. Calling hospitals and the police are good starts. It would also make sense for Cati to be interested in finding out more about White, which she might accomplish with a few creative phone calls to Mags Whitcombe’s or her own friends. If she wants to check in on Ramanuja, she really only needs to call St. Lawrence’s Hospital. Depending on how frank Cati wants to be with her, she might even send Emma out on various errands.

See the out of game blog for posting awards and xp.)

Breaks for the Broken

I.

Thelonius nodded his head and let his weight settle into the crook of Henri’s arm. He lost his rigidity and finally, thankfully, after holding onto a world newly filled with pain and terrors, let himself black out.

Passing willfully into unconsciousness was an uncharacteristic concession for Jones. He was a man who prided himself on his skepticism. Remaining skeptical, he knew, was more a matter of skill and practice than disposition. Maintaining such constant levels of doubt required alertness, active critical faculties, and a great amount of energy. Thelonius was no psychoanalyst, but he knew something about the human mind and the way it directed its energies. It wanted belief, it wanted to accept the situation. Only when the mind was presented with a world that was founded on certitude could it effectively set about solving the problems posed by that world. This was why it was so simple for so many people to accept the most outlandish beliefs: That moral degeneration was just the way of the world. That families could be anything but dysfunctional. That there was a kind, fatherly divinity guiding the faithful. That there was forgiveness for lingering sins. That a ragged jerk from Chicago could make it in New York.

Thel’s dedication to skepticism might have gone a long way towards explaining why, despite his talents, he had never gone very far as a reporter, let along as a reporter of occult circumstances and the unknown. He had never allowed himself to accept the world or his city as it was, as it was presented to him. He couldn’t just write the story. He had to pry it open. New York City – after London, the second biggest city in the world – was a city built on dreams, or so went the cliché, and as such it was a disorderly pile of dislocated desires. Thelonius was attracted to the darker fantasies of the metropolis’s residents, and it was his prerogative to dissemble each of them. Like a physicist, he reduced them into their smallest, most rational elements, forestalling belief until he could grasp each of a dream’s tiniest components. In a way, he was a mechanic of fantasies, taking them apart and putting them back together in a new way, in a way that made sense.

Then one of those fantasies refused to be dissembled. It had reached out from the pile of New York fantasies, grabbed Thel by the nape of his neck, and tried to dissemble him.

He had hung on for that moment for so long. Passing out – relaxing his alertness and doubt, finally allowing his skeptical faculties to enter a state of quietude – was the least Thelonius could do. He knew it was okay to let his eyes close, to let his consciousness go grey. He deserved a break.

II.

People came to New York in search of new lives, wasn’t that the story? Not just immigrants, but Americans too. Americans and foreigners alike, anyone who wasn’t born in the city, shared a kind of faith – a faith that here, with a hard work, they’d find something new and worthwhile. A few newcomers found their ways into New York City by following paths paved with their own ambitions. They fled from nothing, and good for them. Many others were leaving behind poverty. Others fled countries ruined by misgovernment, corruption, warfare, famine. Henri had seen something of that – abroad, but also in the faces of the city’s destitute. The suffering of New York City was a chimera pieced together by the woes of millions of people from thousands of lands. A few were refugees of another kind, leaving behind adversities of an intangible or personal nature. They were all, in some way, Henri’s people, though he couldn’t always bring himself to admit it. Henri had achieved some repute here, and his station

– success earned with his own creativity and labor, a real American dream -

afforded him some social insulation, which separated him from majority of immigrants, wherever their origins. He made his ladies beautiful, and they made him who he was: Monsieur Henri.

“He’s going to live,” Doctor Cherry had said, “There will be scarring. Some internal damage, perhaps. He will have to stay here for a some time; a few weeks at minimum.” That was the lucky part, and a relief to Henri – sadly, it was already easy for Henri to believe that a man could survive injuries such as the ones Thelonius had suffered. The misadventure of Henri’s association with Thelonius, as young as it was, was drawing energy away from Henri’s work, from his ladies, and from everything that Henri had worked hard to earn these past few years. When Cherry had asked, “Mister DuMonde: what happened to Mister Jones?” Henri had been forced to struggle for an answer. He had settled for a lie, and told the doctor that it had been an accident.

The doctor had taken his arm gently, insistently, and pulled Henri to the side of the corridor. “Sir, you’re not being completely honest.” Henri was not ashamed of his lie, for often lying or padding the truth was simply the socially correct thing to do, and he was certainly not harming anyone by avoiding the defiant truth of monsters and wizards. Yet, dishonesty has a way of compounding itself, and the greater untruths upon which most persons’ lives are founded tend to slither out and build connections with all of the peripheral fibs that accumulate during one’s time.

Henri was acutely aware of the precariousness of piling lies upon lies, and this was why he had answered the doctor’s question with a sharp, “Oui, but – it is better that you do not know everything.” Henri’s tone towards the doctor had been slightly paternal, overtly annoyed, and very serious. He was exhausted. He had felt his left eye quiver in its socket, and had caught himself wondering if the doctor had seen it shaking.

Maybe he had. Doctor Cherry had swallowed and given Henri a long look before he said, “Okay,” and relaxed his grip on Henri’s arm. “I don’t know what you people – that swami and the rest of you – are playing at. It’s exacting a toll on your health, to be sure. In my opinion, you should take some time off from it. From everything. You look tired.”

Henri had broken from Cherry’s gaze to turn his eyes back down the hallway towards Thelonius’s room. Henri felt tired. But a break would have meant leaving his business in the hands of his assistants – or closing it down altogether – for a couple of weeks. Now, sitting by Thelonius’s side, fondling the tri-folded pamphlet that Cherry had given him, Henri wondered if that wouldn’t be enough to kill his New York dream. He did, after all, work in the world of fashion, and fashion was nothing if not ephemeral. To abandon it for two weeks might cost him more than money.

III.

There was a knock at the door. It opened just enough for a man to peek his head in.

“Captain Delaney,” Henri said wearily, none too enthused about the police officer’s arrival. He forced the pamphlet back into his pocket.

Before Henri could begin to explain Thel’s condition, Delaney cut him off. “I already know. Listen.” He clutched his hat and another manila envelope. “It was the mob,” he said, looking over his shoulder. “Can I sit down?”

Henri directed Delaney to the chair at the foot of Thel’s bed.

“A mob hit,” the captain explained as he came in. “Louie Two-Piece was in there and now he’s dead.” His eyes narrowed as he talked, and he shut the door. “Do I believe that anybody – anybody – as gunning for Two-Piece? Maybe. He was a shithead, pardon my language.” His hair was mussed and his collar was showing signs of sweat stains. “Now, do I believe that anybody might murder the guy by gouging his eye out with a bottle of Perrier and then walking away just to let him bleed to death? No, but that’s how it was delivered to me. Signed, stamped, and delivered. Two-Piece was still kicking when I got there. Kicking and screaming about his eye. Goddamned sloppy job if it was a hit!”

Henri could scarcely imagine how the man had fallen so as to jam a water bottle into his eye socket. Just as difficult to grasp was why Delaney, the politely overbearing officer from the 33rd precinct, the very man who had met them after the debacle at Gerloch’s home, was letting Henri have such easy access to what was surely guarded police business

Delaney sat down. “But it wasn’t. Of course it wasn’t. There were a dozen other injuries. Bullets in the wall, but only one guy was shot. A bus boy, or someone – just a kid – who’d want to shoot him?” Against his will, Henri thought of Cati, and wondered what she was doing. Delaney continued. “Between you and me and him,” he said, jabbing thumb at Thelonius’s resting body, “I know that you know that we three know a lot more than we’re supposed to know. But you know a lot more than I do – I think. I can’t put it together. And maybe I should keep it that way.” Delaney bit the corner of his pale lip and bowed his head. “Maybe I don’t need to know.”

“But. I saw the scene. I saw the two of yous and that pretty European bird leaving the scene.” Delaney lifted his face and chopped the air with his hand as he spoke. It sounded to Henri as if he might be getting ready to scold him. “Just happened to be around, you know. So. Where is the girl?” He paused for a second, but Henri had no immediate answer for him.

Truthfully, the dressmaker did not know where Cati and Emma had gone; he and Jones had lost them in the crowd escaping The Cellar the night before. Henri thought that they had been with the tuxedoed doctor. Henri shrugged.

Delaney grunted. “I hope you didn’t get her into more trouble than she can handle.” He was no longer squinting. His pale, scolding eyes were bearing down on Henri. “Nobody inside saw anything.” His gaze wandered as he recollected the testimonies of the patrons. “One second they’re sitting around having their drinks – oh, that’s old news in the department by the way, no one’s surprised – and the next second, everything’s come to pieces and they’re all torn and bleeding. That’s the story I kept getting. Before the chief passed word that we oughtta see to other cases. But –” he sighed “– it’s not for nothing that I have this badge. Two people died last night. Look at Thelonius! He looks like he took a sledge hammer in his face!”

True enough. Thel’s wounds looked even worse now that they had dried and were partially covered with rust-soaked bandages. His nose had needed straightening. Both of his lips were split. Two teeth had come out. His face was one spreading purple-black bruise. One eye was covered with a patch, and the other seemed sealed with a crust of dried tears and blood. That was only the external wounds. Cherry had indicated that there were internal injuries as well.

“I don’t like laying off. Just look at this. It’s atrocious. But there’s not going to be any investigation, if you follow me. Because maybe The Cellar is beyond the pale.” Delaney shook his head. “I saw the wreck. There were marks . . . look, was there –” Delaney drew breath. “Was there an animal in The Cellar? I mean, somethin’ big, like a bear. Is that what did this to Jones? If it was an animal, why didn’t anyone see it?”

Henri didn’t answer.

“Damn it,” Delaney sighed, shaking his head again. “Damn.”

Henri watched him remove the manila envelope from beneath his hat.

“This –” Delaney switched the folder from his left to his right hand by way of a shrug “– would just sit in a box in a locker if I didn’t pull it up. It was in a jacket in the bathroom. No ID on the jacket – light grey, cotton, nice material, designer label. The sort of thing a man with some taste might notice, Mister DuMonde. There was a mess of candles and marks in a stall too. A knife with an engraved handle. You remember any of this? Hookum, Jones’s especiality. The department took some photos, but I have a feeling you don’t need any of those.”

All this time, he had been fidgeting with the envelope. He handed it to Henri. “I thought Jones could figure it out. But, uh – ”

“No, you can give it to me.” It was Thelonius. Henri was not sure how long he had been awake and listening to the conversation, but he was thankful that the reporter could join them now and help them decide on a course of action.

Delaney visibly relaxed. “Nice of you to finally join us, Jones. Happy to see you’re not in a coma.”

(Thelonius, Henri, and Captain Delaney are sitting in a room on the third floor of St. Lawrence’s Hospital, where Ramanuja was or is. It is about eight o’clock in the morning, the day after the ruckus at The Cellar. The date is 30 April, 1924, and it’s about ten o’clock in the morning.

Thelonius’s hit points are seriously reduced. His total is currently 5 hit points. Cherry’s recommendation is three weeks bed rest under medical supervision. Given continuous medical care, the prognosis is good, and his hit points will recover fully. Thelonius feels like he might be able to push it and leave the hospital before that, but that would also incur physical consequences for him, which would include and go beyond a reduced rate of hit point recovery.

Henri’s body is in much better shape. His hit points are at their full value of 12 hit points again, but the wear of the supernatural upon his mind is significant. He is wise enough to know that he should seriously consider Dr. Cherry’s suggestion and seek some psychiatric help. He does not need to go to the sanitarium recommended by Cherry, but it would be easier to maintain face that way than it would if he checked into an institution inside the city.

To help clarify your options for action, I can make the following suggestions, which would be obvious to your player characters: Neither continuing the conversation with Delaney nor checking in on Ramanuja would require leaving the hospital. Finding Cati might be a little more difficult, but could start with a phone call. Tracking down Mr. White or Spider makes good sense for different reasons, but will probably require going out into the city. Over longer periods of time, such as those required for physical and mental recovery, studying clues, experimenting with the astral state, and even attempting to learn the procedures and recitations outlined in the various documents that Henri and Thelonius have procured over the course of their tribulations might be productive.

Thelonius currently has Cati’s vial in his jacket.

Please see the out of game blog for posting awards and xp.)

Thelonius nodded his head and let his weight settle into the crook of Henri’s arm. He lost his rigidity and finally, thankfully, after holding onto a world newly filled with pain and terrors, let himself black out.

Passing willfully into unconsciousness was an uncharacteristic concession for Jones. He was a man who prided himself on his skepticism. Remaining skeptical, he knew, was more a matter of skill and practice than disposition. Maintaining such constant levels of doubt required alertness, active critical faculties, and a great amount of energy. Thelonius was no psychoanalyst, but he knew something about the human mind and the way it directed its energies. It wanted belief, it wanted to accept the situation. Only when the mind was presented with a world that was founded on certitude could it effectively set about solving the problems posed by that world. This was why it was so simple for so many people to accept the most outlandish beliefs: That moral degeneration was just the way of the world. That families could be anything but dysfunctional. That there was a kind, fatherly divinity guiding the faithful. That there was forgiveness for lingering sins. That a ragged jerk from Chicago could make it in New York.

Thel’s dedication to skepticism might have gone a long way towards explaining why, despite his talents, he had never gone very far as a reporter, let along as a reporter of occult circumstances and the unknown. He had never allowed himself to accept the world or his city as it was, as it was presented to him. He couldn’t just write the story. He had to pry it open. New York City – after London, the second biggest city in the world – was a city built on dreams, or so went the cliché, and as such it was a disorderly pile of dislocated desires. Thelonius was attracted to the darker fantasies of the metropolis’s residents, and it was his prerogative to dissemble each of them. Like a physicist, he reduced them into their smallest, most rational elements, forestalling belief until he could grasp each of a dream’s tiniest components. In a way, he was a mechanic of fantasies, taking them apart and putting them back together in a new way, in a way that made sense.

Then one of those fantasies refused to be dissembled. It had reached out from the pile of New York fantasies, grabbed Thel by the nape of his neck, and tried to dissemble him.

He had hung on for that moment for so long. Passing out – relaxing his alertness and doubt, finally allowing his skeptical faculties to enter a state of quietude – was the least Thelonius could do. He knew it was okay to let his eyes close, to let his consciousness go grey. He deserved a break.

II.

People came to New York in search of new lives, wasn’t that the story? Not just immigrants, but Americans too. Americans and foreigners alike, anyone who wasn’t born in the city, shared a kind of faith – a faith that here, with a hard work, they’d find something new and worthwhile. A few newcomers found their ways into New York City by following paths paved with their own ambitions. They fled from nothing, and good for them. Many others were leaving behind poverty. Others fled countries ruined by misgovernment, corruption, warfare, famine. Henri had seen something of that – abroad, but also in the faces of the city’s destitute. The suffering of New York City was a chimera pieced together by the woes of millions of people from thousands of lands. A few were refugees of another kind, leaving behind adversities of an intangible or personal nature. They were all, in some way, Henri’s people, though he couldn’t always bring himself to admit it. Henri had achieved some repute here, and his station

– success earned with his own creativity and labor, a real American dream -

afforded him some social insulation, which separated him from majority of immigrants, wherever their origins. He made his ladies beautiful, and they made him who he was: Monsieur Henri.

“He’s going to live,” Doctor Cherry had said, “There will be scarring. Some internal damage, perhaps. He will have to stay here for a some time; a few weeks at minimum.” That was the lucky part, and a relief to Henri – sadly, it was already easy for Henri to believe that a man could survive injuries such as the ones Thelonius had suffered. The misadventure of Henri’s association with Thelonius, as young as it was, was drawing energy away from Henri’s work, from his ladies, and from everything that Henri had worked hard to earn these past few years. When Cherry had asked, “Mister DuMonde: what happened to Mister Jones?” Henri had been forced to struggle for an answer. He had settled for a lie, and told the doctor that it had been an accident.

The doctor had taken his arm gently, insistently, and pulled Henri to the side of the corridor. “Sir, you’re not being completely honest.” Henri was not ashamed of his lie, for often lying or padding the truth was simply the socially correct thing to do, and he was certainly not harming anyone by avoiding the defiant truth of monsters and wizards. Yet, dishonesty has a way of compounding itself, and the greater untruths upon which most persons’ lives are founded tend to slither out and build connections with all of the peripheral fibs that accumulate during one’s time.

Henri was acutely aware of the precariousness of piling lies upon lies, and this was why he had answered the doctor’s question with a sharp, “Oui, but – it is better that you do not know everything.” Henri’s tone towards the doctor had been slightly paternal, overtly annoyed, and very serious. He was exhausted. He had felt his left eye quiver in its socket, and had caught himself wondering if the doctor had seen it shaking.

Maybe he had. Doctor Cherry had swallowed and given Henri a long look before he said, “Okay,” and relaxed his grip on Henri’s arm. “I don’t know what you people – that swami and the rest of you – are playing at. It’s exacting a toll on your health, to be sure. In my opinion, you should take some time off from it. From everything. You look tired.”

Henri had broken from Cherry’s gaze to turn his eyes back down the hallway towards Thelonius’s room. Henri felt tired. But a break would have meant leaving his business in the hands of his assistants – or closing it down altogether – for a couple of weeks. Now, sitting by Thelonius’s side, fondling the tri-folded pamphlet that Cherry had given him, Henri wondered if that wouldn’t be enough to kill his New York dream. He did, after all, work in the world of fashion, and fashion was nothing if not ephemeral. To abandon it for two weeks might cost him more than money.

III.

There was a knock at the door. It opened just enough for a man to peek his head in.

“Captain Delaney,” Henri said wearily, none too enthused about the police officer’s arrival. He forced the pamphlet back into his pocket.

Before Henri could begin to explain Thel’s condition, Delaney cut him off. “I already know. Listen.” He clutched his hat and another manila envelope. “It was the mob,” he said, looking over his shoulder. “Can I sit down?”

Henri directed Delaney to the chair at the foot of Thel’s bed.

“A mob hit,” the captain explained as he came in. “Louie Two-Piece was in there and now he’s dead.” His eyes narrowed as he talked, and he shut the door. “Do I believe that anybody – anybody – as gunning for Two-Piece? Maybe. He was a shithead, pardon my language.” His hair was mussed and his collar was showing signs of sweat stains. “Now, do I believe that anybody might murder the guy by gouging his eye out with a bottle of Perrier and then walking away just to let him bleed to death? No, but that’s how it was delivered to me. Signed, stamped, and delivered. Two-Piece was still kicking when I got there. Kicking and screaming about his eye. Goddamned sloppy job if it was a hit!”

Henri could scarcely imagine how the man had fallen so as to jam a water bottle into his eye socket. Just as difficult to grasp was why Delaney, the politely overbearing officer from the 33rd precinct, the very man who had met them after the debacle at Gerloch’s home, was letting Henri have such easy access to what was surely guarded police business

Delaney sat down. “But it wasn’t. Of course it wasn’t. There were a dozen other injuries. Bullets in the wall, but only one guy was shot. A bus boy, or someone – just a kid – who’d want to shoot him?” Against his will, Henri thought of Cati, and wondered what she was doing. Delaney continued. “Between you and me and him,” he said, jabbing thumb at Thelonius’s resting body, “I know that you know that we three know a lot more than we’re supposed to know. But you know a lot more than I do – I think. I can’t put it together. And maybe I should keep it that way.” Delaney bit the corner of his pale lip and bowed his head. “Maybe I don’t need to know.”

“But. I saw the scene. I saw the two of yous and that pretty European bird leaving the scene.” Delaney lifted his face and chopped the air with his hand as he spoke. It sounded to Henri as if he might be getting ready to scold him. “Just happened to be around, you know. So. Where is the girl?” He paused for a second, but Henri had no immediate answer for him.

Truthfully, the dressmaker did not know where Cati and Emma had gone; he and Jones had lost them in the crowd escaping The Cellar the night before. Henri thought that they had been with the tuxedoed doctor. Henri shrugged.

Delaney grunted. “I hope you didn’t get her into more trouble than she can handle.” He was no longer squinting. His pale, scolding eyes were bearing down on Henri. “Nobody inside saw anything.” His gaze wandered as he recollected the testimonies of the patrons. “One second they’re sitting around having their drinks – oh, that’s old news in the department by the way, no one’s surprised – and the next second, everything’s come to pieces and they’re all torn and bleeding. That’s the story I kept getting. Before the chief passed word that we oughtta see to other cases. But –” he sighed “– it’s not for nothing that I have this badge. Two people died last night. Look at Thelonius! He looks like he took a sledge hammer in his face!”

True enough. Thel’s wounds looked even worse now that they had dried and were partially covered with rust-soaked bandages. His nose had needed straightening. Both of his lips were split. Two teeth had come out. His face was one spreading purple-black bruise. One eye was covered with a patch, and the other seemed sealed with a crust of dried tears and blood. That was only the external wounds. Cherry had indicated that there were internal injuries as well.

“I don’t like laying off. Just look at this. It’s atrocious. But there’s not going to be any investigation, if you follow me. Because maybe The Cellar is beyond the pale.” Delaney shook his head. “I saw the wreck. There were marks . . . look, was there –” Delaney drew breath. “Was there an animal in The Cellar? I mean, somethin’ big, like a bear. Is that what did this to Jones? If it was an animal, why didn’t anyone see it?”

Henri didn’t answer.

“Damn it,” Delaney sighed, shaking his head again. “Damn.”

Henri watched him remove the manila envelope from beneath his hat.

“This –” Delaney switched the folder from his left to his right hand by way of a shrug “– would just sit in a box in a locker if I didn’t pull it up. It was in a jacket in the bathroom. No ID on the jacket – light grey, cotton, nice material, designer label. The sort of thing a man with some taste might notice, Mister DuMonde. There was a mess of candles and marks in a stall too. A knife with an engraved handle. You remember any of this? Hookum, Jones’s especiality. The department took some photos, but I have a feeling you don’t need any of those.”

All this time, he had been fidgeting with the envelope. He handed it to Henri. “I thought Jones could figure it out. But, uh – ”

“No, you can give it to me.” It was Thelonius. Henri was not sure how long he had been awake and listening to the conversation, but he was thankful that the reporter could join them now and help them decide on a course of action.

Delaney visibly relaxed. “Nice of you to finally join us, Jones. Happy to see you’re not in a coma.”

(Thelonius, Henri, and Captain Delaney are sitting in a room on the third floor of St. Lawrence’s Hospital, where Ramanuja was or is. It is about eight o’clock in the morning, the day after the ruckus at The Cellar. The date is 30 April, 1924, and it’s about ten o’clock in the morning.

Thelonius’s hit points are seriously reduced. His total is currently 5 hit points. Cherry’s recommendation is three weeks bed rest under medical supervision. Given continuous medical care, the prognosis is good, and his hit points will recover fully. Thelonius feels like he might be able to push it and leave the hospital before that, but that would also incur physical consequences for him, which would include and go beyond a reduced rate of hit point recovery.

Henri’s body is in much better shape. His hit points are at their full value of 12 hit points again, but the wear of the supernatural upon his mind is significant. He is wise enough to know that he should seriously consider Dr. Cherry’s suggestion and seek some psychiatric help. He does not need to go to the sanitarium recommended by Cherry, but it would be easier to maintain face that way than it would if he checked into an institution inside the city.

To help clarify your options for action, I can make the following suggestions, which would be obvious to your player characters: Neither continuing the conversation with Delaney nor checking in on Ramanuja would require leaving the hospital. Finding Cati might be a little more difficult, but could start with a phone call. Tracking down Mr. White or Spider makes good sense for different reasons, but will probably require going out into the city. Over longer periods of time, such as those required for physical and mental recovery, studying clues, experimenting with the astral state, and even attempting to learn the procedures and recitations outlined in the various documents that Henri and Thelonius have procured over the course of their tribulations might be productive.

Thelonius currently has Cati’s vial in his jacket.

Please see the out of game blog for posting awards and xp.)

Thursday, November 12, 2009

The Cellar Collapses

There was only a moment like this: laughter, the tinkle-tinkle of glasses being gently tipped against one another, the murmur of chatting, the gentle knocking sound of hard-soled shoes against wood floors. Very quickly these happier sounds fell away. The tinkling and murmuring seemed to dissolve into the air; the laughter and the footsteps stopped outright.

“Cat-tee? What are you doing?” Leaning on the toppled table and still holding her weapon, Cati threw a look over her shoulder. Only a few yards behind her, Emma was sitting up in her seat, no longer resting her hand in her hands. “You were just . . . what are you doing with a gun?” Something like understanding – but it couldn’t have been – came over Emma’s face as she looked at the patrons around her. Cati lowered her weapon a little and, following her friend's lead, took in the scene.

To Emma’s right, a man laid on the floor with his knees curled into his chest. A pool of blood was quickly spreading beneath him and he started to rock slightly on his side. Cati threw her gaze to her left, to the man who had been knocked onto the floor when Rashfal had thrown her. The joints in his legs had been strangely locked at right angles as if he had been sitting in a chair, but he was spread out flat now. His eyes were wide open but insensible; his pupils seemed as wide as pennies. There was another pool of blood just beginning to form underneath the back of his head.

Now there was sobbing. At the bottom of the staircase, the woman Cati had bumped into in her flight from Rashfal was pulling herself onto her hands and knees with the help of her companion. As she rose, her lips seemed to fall away in a torrent – blood poured from her broken nose and her smashed teeth. She clutched her ruined face. Her sobs came out as sputters and gurgles. She didn’t want to, but Cati could not help looking to the bathroom attendant. He was on the floor, leaning against the wall and pawing at his shoulder with a senseless look on his face. He was alive, but flabbergasted. None of these people could know what had happened in their midst. One second, they had been dining and drinking, laughing and enjoying the company of their peers; and in the next, they were a broken, ghastly mass of injury and pain.

Cati’s sense of responsibility had been lifted from her during her first moments among the be-stilled scenery. As the disastrous melee had worn on, it had slowly began to settle back into place on her narrow shoulders. Now, as the normal flow of events abruptly resumed, responsibility crashed down on her with staggering weight. She let her gun arm drop and she fell to her knees. Cati began to cry. “I did it . . .”

Emma rushed to her side and began to comfort her friend. “It’s alri–” Emma began, but it wasn’t.

The ragged crowd erupted into motion. The moment of collective astonishment at the suddenness of the carnage gave way into a cacophony of panicked screams, pleas for help, and alarmed outbursts. Some parts of the crowd began an uncoordinated shift to the stairway. Other individuals ran to the bar, or began lifting overturned furniture.

“He’s been shot!” someone screamed.

“My hands!”

“I can’t see! Call the police!”

“She needs water!”

“Everybody stay calm!” someone commanded, but no one obeyed.

Shocks of the grey-dressed man’s blonde hair protruded from between Thelonius’s knuckles. His eyes rolled up to meet Thel’s. “Okay. Let me go now,” he hissed.

The bathroom door swung open. “Mister White! Are you okay!” The second bathroom attendant, the one who had accepted the wizard’s sizable tip just minutes ago, had abandoned his post and his basket of towels. “Oh my God! What happened?” he asked Thelonius. “Here, let me help you with him,” he said as he knelt and moved to slip his hands under the wizard’s shoulders. “Was there some kind of earthquake?”

Clutching the saber in his hand, Henri looked to Thelonius, who had not yet released Mister White’s hair from his clutches. A fresh burden of responsibility had fallen upon their shoulders as well.

Mister White meant to snicker, but it came out a cough.

“Cat-tee? What are you doing?” Leaning on the toppled table and still holding her weapon, Cati threw a look over her shoulder. Only a few yards behind her, Emma was sitting up in her seat, no longer resting her hand in her hands. “You were just . . . what are you doing with a gun?” Something like understanding – but it couldn’t have been – came over Emma’s face as she looked at the patrons around her. Cati lowered her weapon a little and, following her friend's lead, took in the scene.

To Emma’s right, a man laid on the floor with his knees curled into his chest. A pool of blood was quickly spreading beneath him and he started to rock slightly on his side. Cati threw her gaze to her left, to the man who had been knocked onto the floor when Rashfal had thrown her. The joints in his legs had been strangely locked at right angles as if he had been sitting in a chair, but he was spread out flat now. His eyes were wide open but insensible; his pupils seemed as wide as pennies. There was another pool of blood just beginning to form underneath the back of his head.

Now there was sobbing. At the bottom of the staircase, the woman Cati had bumped into in her flight from Rashfal was pulling herself onto her hands and knees with the help of her companion. As she rose, her lips seemed to fall away in a torrent – blood poured from her broken nose and her smashed teeth. She clutched her ruined face. Her sobs came out as sputters and gurgles. She didn’t want to, but Cati could not help looking to the bathroom attendant. He was on the floor, leaning against the wall and pawing at his shoulder with a senseless look on his face. He was alive, but flabbergasted. None of these people could know what had happened in their midst. One second, they had been dining and drinking, laughing and enjoying the company of their peers; and in the next, they were a broken, ghastly mass of injury and pain.

Cati’s sense of responsibility had been lifted from her during her first moments among the be-stilled scenery. As the disastrous melee had worn on, it had slowly began to settle back into place on her narrow shoulders. Now, as the normal flow of events abruptly resumed, responsibility crashed down on her with staggering weight. She let her gun arm drop and she fell to her knees. Cati began to cry. “I did it . . .”

Emma rushed to her side and began to comfort her friend. “It’s alri–” Emma began, but it wasn’t.

The ragged crowd erupted into motion. The moment of collective astonishment at the suddenness of the carnage gave way into a cacophony of panicked screams, pleas for help, and alarmed outbursts. Some parts of the crowd began an uncoordinated shift to the stairway. Other individuals ran to the bar, or began lifting overturned furniture.

“He’s been shot!” someone screamed.

“My hands!”

“I can’t see! Call the police!”

“She needs water!”

“Everybody stay calm!” someone commanded, but no one obeyed.

Shocks of the grey-dressed man’s blonde hair protruded from between Thelonius’s knuckles. His eyes rolled up to meet Thel’s. “Okay. Let me go now,” he hissed.

The bathroom door swung open. “Mister White! Are you okay!” The second bathroom attendant, the one who had accepted the wizard’s sizable tip just minutes ago, had abandoned his post and his basket of towels. “Oh my God! What happened?” he asked Thelonius. “Here, let me help you with him,” he said as he knelt and moved to slip his hands under the wizard’s shoulders. “Was there some kind of earthquake?”

Clutching the saber in his hand, Henri looked to Thelonius, who had not yet released Mister White’s hair from his clutches. A fresh burden of responsibility had fallen upon their shoulders as well.

Mister White meant to snicker, but it came out a cough.

Monday, August 10, 2009

The Stillness of the Hunter

The noise of the Cellar receded and disappeared in a “poof” as the front doors swung together and blew a gust of stale air out from the club.

The warmer air from inside circulated around Cati’s ankles. She huffed one last time and looked upward into the stars. On the verge of enjoying a restful breath of night air, she remembered her purse and removed a cigarette.

Henri was at her side holding a match. “Now what, mademoiselle?”

Cati leaned into the matchlight. “Do you think it’s safe to just go home?”

“I do not know.” Henri looked to Thelonius questioningly, but the reporter’s back was to them; he was looking at the interior of the club through the porthole on the front doors. Unencouraged, Henri asked Cati if she would require an escort.

“Oh!” Cati realized. “I had one! Should I tell her I’m leaving?”

Thelonius didn’t turn around. He said, “There’s something wrong.”

“What, did he follow us?”

“See for yourselves.” He stepped away from the tiny windows on the front doors.

Cati and Henri crept up and drew their faces near to the portholes. Inside, the breezeway, the coat room, and the Cellar’s ground floor ballroom, people stood around, striking cockish poses. A man was leaning over the counter at coat check, his hands behind his waist, peering after the attendant. In the breezeway, a woman was approaching him at an exaggerated trot. She stood on her right toe, with her left foot posed in the air ahead, extended almost as a dancer’s. She and the man, and everyone in the ballroom: they were hung in time. The effect was nearly photographic.

Cati pushed open the doors. “Hey! Hey you!” she called, as if upbraiding the Cellar’s patrons. Henri turned to the bouncer, who had been standing by quietly listening. Already assured in his heart of what to expect, Henri snapped his fingers in front of the bouncer’s nose.

Thelonius sized the bouncer up, and wondered just how to capture the scene on film. How does one photograph the act of standing still? Perhaps if he could take a series of pictures with Henri and Cati in them and simulate the passage of time . . . but just what would that be demonstrating? That a roomful of people could stand quietly as Henri and Cati danced among them? At least the wind is blowing, he thought. Then he remembered Rashfal.

The front doors were swinging again. They closed, separating Cati from the men. She tapped the coatless man on the shoulder, to no effect. Behind coat check, the attendant was holding coats apart with his gloved hands, frozen as the others were. “They’re all like this,” she murmured to herself softly. She couldn’t pull her eyes from these people – the old money, the nouveau riche, the descendants of nobility, the gifted young bankers and businessmen – all the people that her family had been mingling with for generations, all the people from whom she had failed to escape time and time again. Before her, a mass of living mannequins, just as she had always known. Finally! she felt like cheering – as though she had for once managed to transcend the stagnant worlds of her father and her husband, the dead foreign bloodlines, the weight of her inheritance and the demands of her ancestors. She smiled and let her hand dip into the man’s pocket. His wallet was there; she dropped it back in; it wasn’t fun this way.

A foul scent wafted in on the breeze, of rot, or of fluids repelled from the innards of an animal. Thelonius caught it and winced.

Henri saw his companion’s face wrinkle and, as if by mimesis, the scent appeared deep within his own nasal passages. It had snuck in. It burned a little and Henri thought to rub his eyes. He remembered a rule of thumb that had been meaningful to him once in a far away place, a truism that he had muttered to himself hundreds of times as a sick kind of reassurance: If you can smell it, you’re in it!

“Thelonius! – we are in danger! We must go back inside now!”

Thelonius would not have disagreed – but in an instant, the wind intensified – Henri saw the streetlights behind Thelonius pull like taffy and blurrily suggest movement – the lights stretched over Thelonius – no, more like something translucent and wet had been flung across points of light – Henri thought to compare it to observing the headlights of an oncoming car through a dirty windshield – it barreled into the reporter – Thelonius fell to the ground, the camera clattered against the cement - the wind turned up into the sky, refracting the lights of buildings' highest windows. The bouncer’s jacket had been disturbed.

Cati pushed open the doors. “Hey! Hey you!” she called, as if upbraiding the Cellar’s patrons. Henri turned to the bouncer, who had been standing by quietly listening. Already assured in his heart of what to expect, Henri snapped his fingers in front of the bouncer’s nose.

Thelonius sized the bouncer up, and wondered just how to capture the scene on film. How does one photograph the act of standing still? Perhaps if he could take a series of pictures with Henri and Cati in them and simulate the passage of time . . . but just what would that be demonstrating? That a roomful of people could stand quietly as Henri and Cati danced among them? At least the wind is blowing, he thought. Then he remembered Rashfal.

The front doors were swinging again. They closed, separating Cati from the men. She tapped the coatless man on the shoulder, to no effect. Behind coat check, the attendant was holding coats apart with his gloved hands, frozen as the others were. “They’re all like this,” she murmured to herself softly. She couldn’t pull her eyes from these people – the old money, the nouveau riche, the descendants of nobility, the gifted young bankers and businessmen – all the people that her family had been mingling with for generations, all the people from whom she had failed to escape time and time again. Before her, a mass of living mannequins, just as she had always known. Finally! she felt like cheering – as though she had for once managed to transcend the stagnant worlds of her father and her husband, the dead foreign bloodlines, the weight of her inheritance and the demands of her ancestors. She smiled and let her hand dip into the man’s pocket. His wallet was there; she dropped it back in; it wasn’t fun this way.

A foul scent wafted in on the breeze, of rot, or of fluids repelled from the innards of an animal. Thelonius caught it and winced.

Henri saw his companion’s face wrinkle and, as if by mimesis, the scent appeared deep within his own nasal passages. It had snuck in. It burned a little and Henri thought to rub his eyes. He remembered a rule of thumb that had been meaningful to him once in a far away place, a truism that he had muttered to himself hundreds of times as a sick kind of reassurance: If you can smell it, you’re in it!

“Thelonius! – we are in danger! We must go back inside now!”

Thelonius would not have disagreed – but in an instant, the wind intensified – Henri saw the streetlights behind Thelonius pull like taffy and blurrily suggest movement – the lights stretched over Thelonius – no, more like something translucent and wet had been flung across points of light – Henri thought to compare it to observing the headlights of an oncoming car through a dirty windshield – it barreled into the reporter – Thelonius fell to the ground, the camera clattered against the cement - the wind turned up into the sky, refracting the lights of buildings' highest windows. The bouncer’s jacket had been disturbed.

Thelonius cursed as Henri crouched and scanned the air around them. Before he even bothered to get up, Thel checked his camera. Henri took note of a drip of blood, trailing from somewhere near Thelonius’ crown, underneath the brim of his hat. Henri pushed a door open. “There is no time! Come!”

(Upon realizing that the world had stopped around him, Thelonius was able to keep it together. Henri and Cati were not able to adjust as well to the realization. Henri has suffered -1 sanity and Cati -2. Due to a surprise attack by goodness-knows-what, Thelonius has suffered -1 hit point. Thelonius and Henri are in combat rounds – please declare your actions. Cati is not in combat yet, but could still act.

Corpus Clock and Chronophage conceived and designed by John Taylor, Stewart Huxley, Matthew Sanderson, and Alan Meeks. Image from A Blog to Read.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)